LOVE IT OR HATE IT: BRUTALIST ARCHITECTURE

Brutalist architecture is one of those styles that feels impossible to be neutral about. People either recoil at the mere thought of it or defend it with near-religious devotion. I’ll be honest: I’m not an architect, and I won’t pretend to know or understand every technical detail or choice behind the style, but I have always been deeply curious about them and how they make us feel. Brutalism, more than almost any other movement, demands a reaction. It’s heavy, stark, and misunderstood, yet somehow it keeps resurfacing in conversations about everything from design to cities and the future of architecture.

What continuously draws me back to the style is the dystopian-esque, cold feeling, and part of that feeling comes from the reason they look the way they do and what they are trying to say.

A Brief History of Brutalist Architecture

Despite how the name sounds, Brutalism isn’t about aggression or anything cruel. The term comes from the French phrase béton brut, which means “raw concrete.” The style emerged in the mid-20th century after World War II, when cities needed to be quickly rebuilt, at scale, and affordably. Functionality was prioritized over look, and the materials became the guiding principle.

Brutalism gained more momentum in the 1950s through the 1970s, particularly in Europe, the United States, and parts of the former Soviet Union. Governments and other institutions embraced it for public buildings like universities, libraries, housing complexes, and civic centers because it felt serious, durable, and suitable for everyone. These buildings were meant to serve the public, not necessarily impress them with luxury.

Over time, many Brutalist structures became associated with urban decay, underfunded public housing, and cold, unwelcoming environments. As architectural tastes shifted toward materials like glass and steel, Brutalism began to fall out of favor, with many buildings left to deteriorate or be demolished.

Characteristics of Brutalism

Brutalism is immediately recognizable. The most defining feature is the use of raw materials, most famously concrete, often left unfinished and textured by molds that shape it. The shapes and forms are bold and geometric with strong lines. The buildings often feel monolithic and almost sculptural. They feel carved rather than assembled. Windows are usually minimal or repetitive, reinforcing a sense of order and function rather than decoration.

There is a sense of honesty to Brutalism. Structural elements are exposed instead of hidden. Pipes, supports, and joints aren’t tucked away or disguised. They are part of the visual language. Whether or not you find it beautiful, Brutalism rarely pretends to be something that it isn’t.

The Modern Reawakening of Brutalism

Recently, Brutalism has experienced something of a cultural revival. Instagram accounts (love them), photography books, and design blogs have reframed these buildings as striking, graphic, and even, at times, poetic. Younger generations, especially those interested in design and urban culture, are seeing Brutalism with fresh eyes.

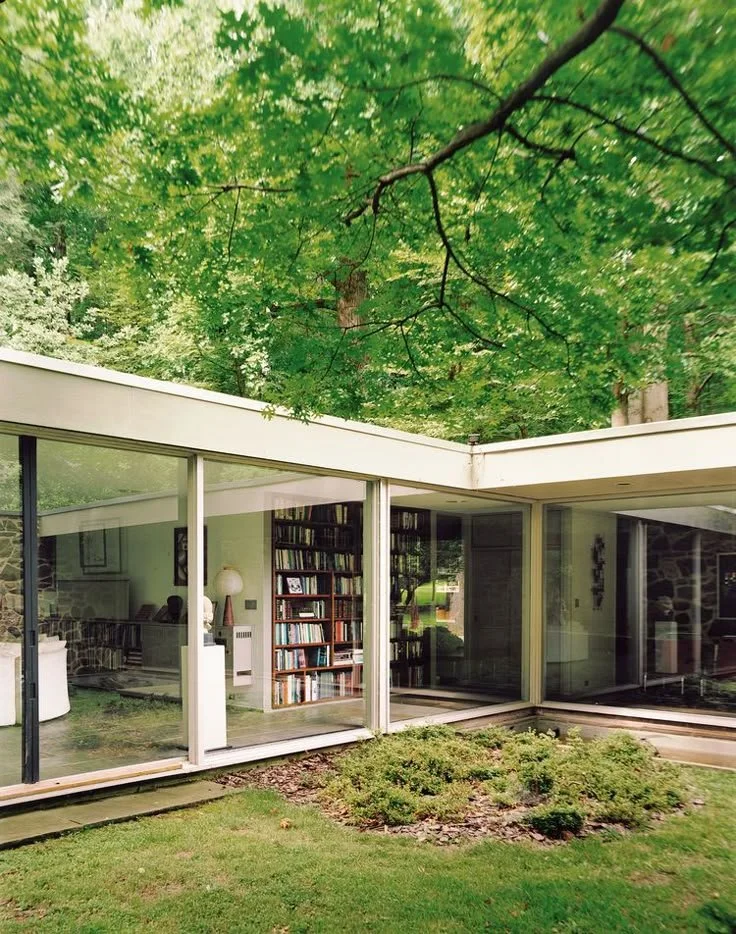

Modern interpretations of the style tend to soften the harsher edges. Architects borrow principles like material honesty, bold forms, and structural clarity while pairing them with warmer elements used today, like wood, greenery, and natural light. Concrete is still central, but it’s much smoother, lighter, and more intentional in its application.

Rather than being used in massive government complexes, contemporary Brutalist-inspired designs show up in museums, private homes, boutique hotels, and cultural spaces. These buildings are more thoughtful, less imposing, and still retain the strength and confidence that defined the original movement.

How Brutalism Is Being Used Today

Brutalism as a style isn’t as dominant as it is a reference point. Designers use it to make statements about sustainability, permanence, and disposable design. In a world that has become dominated by algorithm-friendly aesthetics, Brutalist-inspired architecture feels almost rebellious. There is also a preservation movement gaining traction. Many Brutalist buildings are old enough to be considered historically significant. Efforts to save them often come from communities that have learned to appreciate their uniqueness. These buildings and structures tell stories about postwar optimism, social ambition, and the realities of urban planning. Stories worth remembering, even if the buildings themselves aren’t universally loved.

Learning to Sit with Discomfort

Brutalist architecture brings discomfort to a lot of people and sits with them. It makes us question what we expect buildings to be and consider function alongside beauty. It’s not warm, it’s not delicate, and it’s rarely charming. I find Brutalism fascinating because it refuses to explain itself. It stands there, heavy and unmoving, daring you to either dismiss it or look closer. To confront its dystopian-esque coldness. And maybe that’s why it continues to matter: in a world with polish and perfection, Brutalism reminds us there is value in something raw, honest, and not trying to win anyone over.

get the look

101 Copenhagen Brutus Stool

Silver 3D Wall Art

Monolith Floor Mirror

Paulin Coffee Table

Abstract Wooden Sculpture

Minimalist Brutalist Lounge Chair